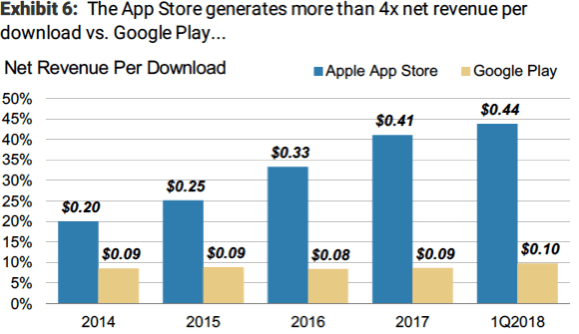

For as long as just about anyone can remember, the amount of money that a user spends on Google Play has been lower than the amount a user spends on the App Store.

Despite Google’s work to improve the store and the impressive range of high-end Android handsets released in the past year, Sensor Tower and Morgan Stanley suggested net revenues per user on its flagship store sat at just $0.10 in Q1 2018. This compares unfavorably with the same metric on the App Store, which was benchmarked at $0.44 in the first three months of the year.

In this context, it’s understandable why Google is apparently considering rolling out a subscription service to access premium content on its store. But for it to succeed, it will need to change the way subscriptions work to suit a mobile context to give it a chance of succeeding.

Subscriptions = good for business

The reason why Play Pass could make sense as a business proposition now is a simple one. We’re living in the era of the subscription economy and consumers are willing to change the way they consume content to adapt to it.

Over the past decade, services such as Netflix, Spotify and Dollar Shave Club have changed the way that consumers access premium products. Rather than paying a price up front for each individual item, consumers instead pay to receive unlimited access to a back catalogue of content or to receive exclusive items at a time of their choosing through one monthly cost.

The benefits of such an approach for business is simple. Provided that you can scale to the point where the service you offer has enough subscribers, you can – theoretically – generate vast revenues consistently on a monthly basis.

Netflix is probably the best example of this in the market today. After spending its early years as an insignificant player in the market, the company’s subscriber base has exploded as a result of its deep back catalogue, original content and brand awareness. In 2017 alone, it generated $11.7bn in revenue – helping it to double down on what had made it successful in the first place.

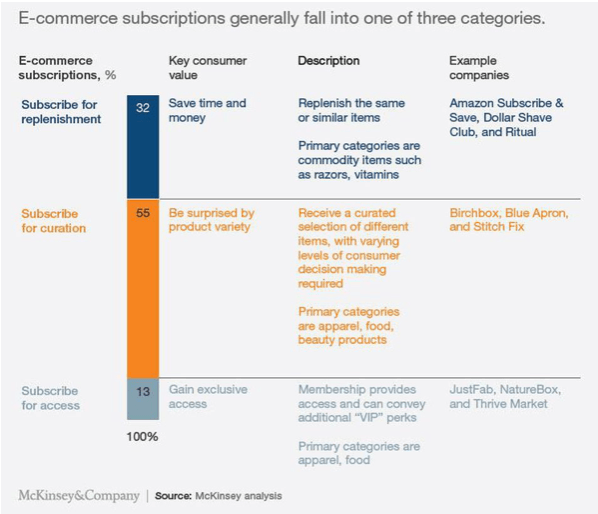

However, it isn’t just businesses who like subscription services; consumers like them too. Research from McKinsey into the buying habits of over 5000 customers in the US found that 46% of consumers brought products through subscription services in 2016.

Provided subscription services offered interestingly curated content, made purchasing a beloved item easy or offered the subscriber exclusive content, consumers were willing to invest in them. And though these points apply to other subscription offerings, they can apply to video game angled offerings too.

Getting into the subscription game?

Subscription models are not new to video game businesses. Players were coughing up monthly fees to play massively multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPGs) World of Warcraft or Runescape way before Netflix was technically able to stream movies. Even Fortnite has a subscription mechanic of its own in the form of the now famous Battle Pass.

Context-aware tech: The secret to 81% more conversions

Learn how leading apps are using context-aware technology to deliver perfectly-timed offers, reduce churn & transform passive users into loyal fans.

Learn more

However, video games companies have tended to use subscriptions as a mechanic for monetizing single games. Until recently, there was little to no concerted effort to use subscription as a mechanic for distributing games.

The emergence of Netflix and Spotify has changed that dynamic. If a single service is able to offer access to thousands of films or millions of songs for under $15 per month, why should consumers pay three or four times as much as that to access a single game?

This position was challenged further by services like Playstation Plus and Twitch Prime. Although neither subscription service is principally about distribution, their offer of free time limited monthly games for subscribers have continued to shape consumer expectations towards subscription services.

This conundrum, along with the necessary technological evolution required to stream content, has paved the way for the emergence of credible video game subscription services in the market.

Offerings such as Microsoft Xbox’s Game Pass, which provides players with access to dozens of older Xbox titles (and some newer ones like Laser League and Forza Horizon 4) for a low-cost monthly subscription fee, have recently hit the market and began filling the gap identified by consumers.

These services have even started to demonstrate that they offer unique value in a way that other services don’t. For example, research by Newzoo has shown that a low cost subscription model appeals specifically to families and could open the console market to new players.

So the question is simple: if subscription works in the wider economy and looks as if it is starting to work in the wider games industry, will such an approach work on mobile?

Potential Play Pass problems

The answer to that question isn’t easy. However, there are good reasons to believe that a distribution service like Play Pass could struggle to make headway on Android.

The first problem is the biggest one: mobile players expect the majority of their games to be released for free.

While there have been brilliant paid mobile games like Monument Valley, Threes, Reigns and Motorsport Manager, free to play games and apps have dominated the sector for years now. This makes it much harder to lock content behind a paywall and make a compelling argument for users to break it down.

The second problem is Android specific. While there is an argument to be made that Play Pass could help convert low spending players into consistent revenue generators, the alternative view is that those players will be equally reluctant to spend on a monthly subscription.

Finally, Play Pass is likely to suffer because it will struggle to meet any of the three criteria outlined by McKinsey. Purchasing through Play Pass will not necessarily be much easier than downloading through the store; interesting curation already takes place within Google Play itself; unless it gains traction, it’ll be unlikely to offer much exclusive content to players.

Summary – an alternative route to long-term success

In short, Play Pass has a lot of barriers to overcome if it is to succeed as a viable traditional subscription service. However, it may make more sense if Google chooses to avoid those barriers altogether by taking a different route to build value.

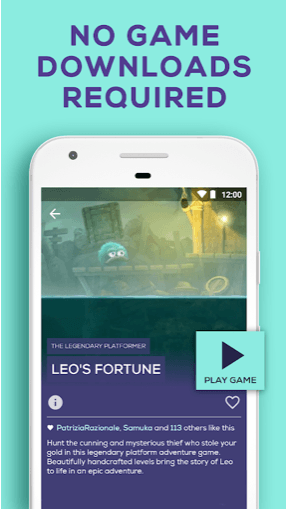

First, it should look at pioneers in the space like Hatch to see how they’re building additional value into a mobile focused service. While Hatch faces many of the problems Play Pass does, its focus on building a community, on allowing “multi-player” interactions in all games and the selling point of game streaming (rather than downloading) adds value.

Second, Google should look at ways of increasing the value of Play Pass by tapping into the free to play economy. It could, perhaps, provide players with credit worth more than their monthly subscription to use in leading free to play titles. This could help justify the cost of entry and provide a hook to players of long-lived service titles.

Finally, Google could also deal with its historically low spending consumers head-on by pricing its service in line with their expectations. If it were, for example, to charge a peppercorn sub $1 rate for entry and support itself further through ad funding, it could gain enough critical mass to drive the service forward.

Google may not be able to achieve success with Play Pass if it follows the norms of subscription services. But if it is willing to rip up the rule book to create a subscription service fit for the mobile gaming economy, it could potentially find a way to thrive in the market.